Carl Mauritz has been one the Brushy Creek Mine's most ardent supporters and has been collecting there for over a decade during his family's annual rockhounding pilgrimages from Wisconsin to western North Carolina. So, when he obtained

permission from the owners to collect there on a Sunday, he called to ask if

Chrissy and I would like to tag along. Naturally we heartily agreed to

accompany Carl and his brother Randy, never being ones to turn down a new

rockhounding opportunity or to hang with our pals. Chrissy was feeling a tad puny that day and didn't feel up to working in the heat, so she cheerfully volunteered to be the camera girl for the day.

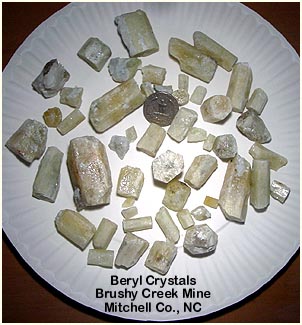

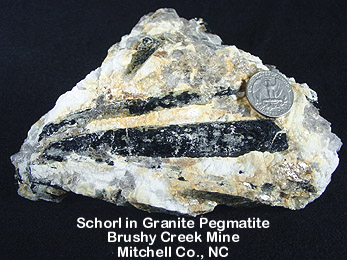

Guided tours of the Brushy Creek Mine are generally conducted by reservation on Saturday mornings during the months of June, July, and August. The mine is best known for its beryl, including common, golden and aquamarine. Other minerals that may be recovered from the granite pegmatite include; tourmaline var. schorl, microcline, garnet, plagioclase, muscovite, apatite, and meta-autunite. It

is no secret that the mine owners salt the floor of mine with various

non-native minerals preceding each tour to ensure that newbie rockhounds find

their money's worth. Since I have not been to the mine during normal operating hours, I am not in a position to endorse its tours. However, more information about the mine may be found by clicking on the following link: Brushy Creek Mine.

non-native minerals preceding each tour to ensure that newbie rockhounds find

their money's worth. Since I have not been to the mine during normal operating hours, I am not in a position to endorse its tours. However, more information about the mine may be found by clicking on the following link: Brushy Creek Mine.

Carl, Randy and I went to work on the boulders that had been left behind by a

recent blast. It didn't take long to discover that tourmaline was the most prevalent accessory pegmatite mineral, although most was broken and shattered. I assumed that the shattered nature of the black crystals was likely caused by combination of weathering and blasting. Within about 5 minutes, Randy was the first to discover a small pale greenish-white beryl crystal in the pegmatite, followed soon after by Carl and myself.

Carl Mauritz

Randy Mauritz

| |

It became

apparent to me that the mine's beryl is found most often in close association with the tourmaline. With this in mind, I turned my attention to the wall of the mine. I followed my nose upward to a likely spot and began banging and prying.

Within about half and hour, I started finding beryl crystals in matrix. I was especially excited because this was the first time that I could

remember where I was able to hunt for beryl in-situ instead recovering it from

Within about half and hour, I started finding beryl crystals in matrix. I was especially excited because this was the first time that I could

remember where I was able to hunt for beryl in-situ instead recovering it from

spoil pile rocks, as at the Ray Mica Mine for instance. As I continued to work the rock, I started finding lots of beryl crystals and tons of tourmaline, however the majority of the crystals were fractured and fell out in pieces from the pegmatite. Nearly all of the beryl crystals were pale yellowish-greenish-white in color,

but a few showed a hint of bluish green and a couple others were golden and semi-gemmy. I managed to recover a few crystals that didn't fall apart and stayed in matrix; while not the highest quality gems that I have ever found, I was nonetheless pleased to obtain specimens from a location that was new to me.

spoil pile rocks, as at the Ray Mica Mine for instance. As I continued to work the rock, I started finding lots of beryl crystals and tons of tourmaline, however the majority of the crystals were fractured and fell out in pieces from the pegmatite. Nearly all of the beryl crystals were pale yellowish-greenish-white in color,

but a few showed a hint of bluish green and a couple others were golden and semi-gemmy. I managed to recover a few crystals that didn't fall apart and stayed in matrix; while not the highest quality gems that I have ever found, I was nonetheless pleased to obtain specimens from a location that was new to me.

Like the beryl, the tourmaline crystals were nearly all tapered from one end to the other along their length. Although I am a geologist, I don't know why the crystals formed in this peculiar manner.

While I was banging, I noticed some tiny grass-green colored flecks on tourmaline. Although I could have used a loop or at least some reading glasses to better see the small crystals, based on my experience at other area pegmatites, I guessed that the mineral was either tobernite or meta-autunite. Sure enough, when I got home I was able to determine that the green mineral was indeed meta-autunite. The easiest way to tell the difference between meta-autunite and torbernite is that the former is fluorescent under shortwave ultraviolet light whereas the latter is not. The following two pictures show one of the meta-autunite specimens.

As we were packing up to leave, Carl noticed a bright flash of orange beneath some trees next to the mine. Upon closer inspection, he discovered that the color was a beautiful clump of mushrooms. As my southern friends would say, "they ain't rocks, but sure are purdy!"

I would later find out by contacting Ken McGill with the Asheville Mushroom Club (AMC) that the bright orange fungi are aptly named "Jack O'Lantern Mushrooms" or "Omphalotus olearius". Thanks to Ken for his help! If you are interested in more information about western North Carolina mushrooms, be sure to check out the AMC website at

www.main.nc.us/amc/.

Thanks also to Carl for setting up the trip. Except for all the cramps that I ended up getting from working way too hard and long in the way too hot sun, we had a blast! You da man, Carlyle!

CLICK THE LITTLE MINER TO RETURN TO THE FIELD TRIP PAGE