I peered into a narrow tunnel that had been blasted over five decades earlier

into solid rock by steel-hard western North Carolina mica miners. Two feet

of ice-clear water on the floor and a modicum of good sense dissuaded me

from venturing into the darkness, although I did feel drawn to the idea of

what could be seen where natural light had never shone. Maybe if I stood

there and listened hard and long enough, I would be able to hear the

timeless echoes from a rock drill, hoist engine or men joking with each

other while taking a well-earned cigarette break.

“Them old boots yer a wearin is starting to get a bit ripe ain’t they

Bassey?”

“You got a point there, Yates, but I’m a waitin fer these olduns to rot

clean off my feet afore I git me another pair”, replied Bassey with a wink.

But, overhearing a conversation from days gone by was not to be that day and

the only sound was from water cascading its way ever downward in nearby

mountain stream.

Earlier that day, I set out from our home near Asheville, North Carolina. My main goal was to visit the Cattail Mine located on the southern flank of Grassy Knob Ridge near Pensacola in Yancey County, North Carolina. I had discovered the former muscovite and feldspar mine while perusing the literature, including old state and federal geological publications. Old mines, such as the Cattail, are great locations to prospect for rock and mineral specimens, so I will often track down these abandoned mines to see what they have to offer. While it is always my desire to find a choice specimen and I hoped to do just that in the Cattail Mine’s abandoned spoil piles, I was also keenly interested in the history and geology of the mine.

Modern rock and gem collecting in western North Carolina began as an extension of the commercial mining of rocks and minerals. Exotic gems such as aquamarine, emerald, and garnet are commonly found where mica was mined from granite pegmatites. A pegmatite is a very coarse-grained igneous rock that has an average grain size of 20 mm or more. Muscovite is a flexible form of mica and its sheets were once used as windows in the doors of wood and coal burning stoves. This application was called isinglass. It was also used for radio tube insulators in the early to middle 20th Century. Muscovite is used today as a special additive in certain industrial products, such as drywall joint compound, sheet rock joint cement, plastics, paint and oil well drilling fluids. It is also used as an electrical insulator, automobile metallic flake paint and in women’s make-up (from www.mitchell-county.com/festival/spminingdistrict.html). During mining operations, a mica miner’s only interest was to recover as much mica as he could. He was not interested in any other mineral besides what he was paid to recover and would help feed his family. Ironically, many of the minerals discarded as nuisances by mica miners would decades later become far more valuable the mica itself.

The Cattail Mine, formerly known as the Isom Mine, was discovered and, perhaps, first worked, in the late 1800’s by Isom Silvers, an entrepreneur from Pennsylvania. As is often the case with mica mines in western North Carolina, there is some debate as to the name of this mine. Lowell Presnell, who is a life-long Yancey County resident, descendant of many local mica miners, and author of a book titled “Mines Miners and Minerals of Western North Carolina’s Mountain Empire”, claims in personal correspondence that the Cattail and Isom Mines are two separate mines. However, two geologic publications and a 1952 newspaper article (listed as references in preceding paragraphs) indicate that the Cattail and the Isom are two names for the same location. With all due respect to my friend, Lowell, and knowing that he may indeed by correct, I will nonetheless use the name “Cattail Mine" in this report.

The Cattail Mine was periodically operated by numerous interests during the early to mid-20th Century for mostly muscovite and some feldspar. Mica books as large as 800 pounds were reportedly recovered from the mine. Bill Rice leased the property in 1904 to Will and Jess Silvers and B. Rolland all of Yancey County who operated the mine until 1906. Between

1924 and 1925, J.E. Burleson deepened the shaft that had been started earlier by a Mr. Isham. Operators during the 1929-32 period were Threadgill and Moffat, T.R. Burleson, Celo Mining Company, Floyd Wheeler, Fortner and Edge,

D.L. McMahan, and D.R. and W.H. Bailey. In 1934, a Mr. Fouts of Florida de-watered the mine and installed a cableway for transporting feldspar from the mine, but the operation was unsuccessful and was soon thereafter discontinued. A few parts of the cableway can be found scatted in the forest and it still appears on the USGS topographic map. Lee Ray of Pensacola re-opened the mine on May 14, 1943 and operated it along with Rex Yelton until W.E. Loughridge took over in the fall of 1943. An unknown operator again operated the mine briefly in 1949. However, groundwater that had filled the bottom of the 210-ft deep vertical shaft finally made mining too difficult to continue or at least this was the case until late 1951. (from USGS Strategic Minerals Investigation Report, “Cattail Mica Mine, Yancey County, North Carolina” by J.C. Olson, 1944 and Greensboro Daily News, “Tar Heel Mica Mines Filling Vital Defense Needs” by Robert H. Fowler, November 23, 1952)

1924 and 1925, J.E. Burleson deepened the shaft that had been started earlier by a Mr. Isham. Operators during the 1929-32 period were Threadgill and Moffat, T.R. Burleson, Celo Mining Company, Floyd Wheeler, Fortner and Edge,

D.L. McMahan, and D.R. and W.H. Bailey. In 1934, a Mr. Fouts of Florida de-watered the mine and installed a cableway for transporting feldspar from the mine, but the operation was unsuccessful and was soon thereafter discontinued. A few parts of the cableway can be found scatted in the forest and it still appears on the USGS topographic map. Lee Ray of Pensacola re-opened the mine on May 14, 1943 and operated it along with Rex Yelton until W.E. Loughridge took over in the fall of 1943. An unknown operator again operated the mine briefly in 1949. However, groundwater that had filled the bottom of the 210-ft deep vertical shaft finally made mining too difficult to continue or at least this was the case until late 1951. (from USGS Strategic Minerals Investigation Report, “Cattail Mica Mine, Yancey County, North Carolina” by J.C. Olson, 1944 and Greensboro Daily News, “Tar Heel Mica Mines Filling Vital Defense Needs” by Robert H. Fowler, November 23, 1952)

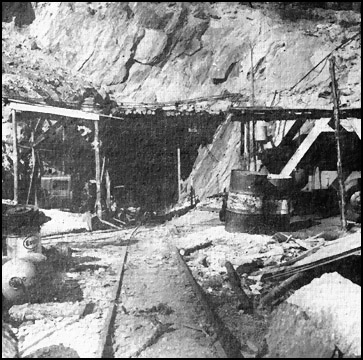

In 1951, the Yancey Mica Mining Corporation was formed. It was composed of

Yates R. Bennett, president; his second cousin, Mark W. Bennett, vice president; W.J. Godfrey, general manager; and D.M. Robinson, secretary. One major goal of the corporation was to re-open the Cattail Mine to take advantage of the high prices for muscovite that the federal government’s Defense Mineral Authority was set to pay until 1955. However, in order to do so, the mine would have to be de-watered to access the pegmatite at the bottom of the deep shaft. On the advice of the Bureau of Mines, the operators decided to tunnel into the side of the mountain and aim for the vein near the bottom of the water-filled shaft. The plan would allow the water to flow out the tunnel so that the pegmatite could again be worked. It was estimated at the time that the tunnel would have to extend to at least 500 feet and, needless to say, intersecting the shaft would be quite an engineering feat. (from Greensboro Daily News, “Tar Heel Mica Mines Filling Vital Defense Needs” by Robert H. Fowler, November 23, 1952)

Yates R. Bennett, president; his second cousin, Mark W. Bennett, vice president; W.J. Godfrey, general manager; and D.M. Robinson, secretary. One major goal of the corporation was to re-open the Cattail Mine to take advantage of the high prices for muscovite that the federal government’s Defense Mineral Authority was set to pay until 1955. However, in order to do so, the mine would have to be de-watered to access the pegmatite at the bottom of the deep shaft. On the advice of the Bureau of Mines, the operators decided to tunnel into the side of the mountain and aim for the vein near the bottom of the water-filled shaft. The plan would allow the water to flow out the tunnel so that the pegmatite could again be worked. It was estimated at the time that the tunnel would have to extend to at least 500 feet and, needless to say, intersecting the shaft would be quite an engineering feat. (from Greensboro Daily News, “Tar Heel Mica Mines Filling Vital Defense Needs” by Robert H. Fowler, November 23, 1952)

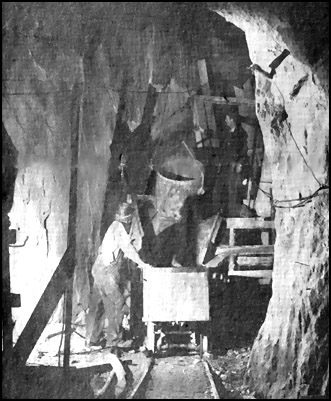

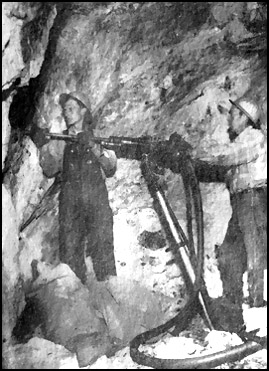

Amos Presnell of Yancey County was hired to construct the tunnel at the Cattail. He and his crew began tunneling operations in the snow on Christmas day 1951. Working nearly around the clock, they chiseled with two mounted

jackhammers with tungsten-carbide drills and blasted through solid rock. Five feet a day was considered excellent progress, while four was an average rate. As the men got nearer to where they hoped to intersect the shaft, there was some real concern that the rock between the shaft and tunnel could give way all at once and a flood of water would shoot them and their equipment down the side of the mountain. Five months and 521 feet later, Amos was drilling to blast when they finally broke through. Fortunately, the rock held and they drilled extra holes upward that allowed the water to slowly drain out. The remaining rock was removed to unite the shaft and the tunnel. That part of their task behind them, the men dug down and discovered a very rich vein. The hardy

miners worked this vein downward and recovered a great volume of mica until the US Government subsidy ended in 1955 (from Greensboro Daily News, “Tar Heel Mica Mines Filling Vital Defense Needs” by Robert H. Fowler, November 23, 1952 and “Mines Miners and Minerals of Western North Carolina’s Mountain Empire by Lowell Presnell, 1999).

jackhammers with tungsten-carbide drills and blasted through solid rock. Five feet a day was considered excellent progress, while four was an average rate. As the men got nearer to where they hoped to intersect the shaft, there was some real concern that the rock between the shaft and tunnel could give way all at once and a flood of water would shoot them and their equipment down the side of the mountain. Five months and 521 feet later, Amos was drilling to blast when they finally broke through. Fortunately, the rock held and they drilled extra holes upward that allowed the water to slowly drain out. The remaining rock was removed to unite the shaft and the tunnel. That part of their task behind them, the men dug down and discovered a very rich vein. The hardy

miners worked this vein downward and recovered a great volume of mica until the US Government subsidy ended in 1955 (from Greensboro Daily News, “Tar Heel Mica Mines Filling Vital Defense Needs” by Robert H. Fowler, November 23, 1952 and “Mines Miners and Minerals of Western North Carolina’s Mountain Empire by Lowell Presnell, 1999).

Mica-bearing pegmatites occur throughout North Carolina’s Blue Ridge province, but are concentrated in the Spruce Pine and Franklin Districts. The Cattail Mine is located within the Spruce Pine district. The average mineral content of the Spruce Pine pegmatites is oligoclase, quartz, perthitic-microcline and muscovite. Accessory minerals include biotite, garnet, apatite, allanite, beryl, epidote, thulite, pyrite and pyrrhotite. Some pegmatites contain certain other trace minerals that are too numerous to mention in this article. (from “Mica Deposits of the Blue Ridge in North Carolina, Geological Survey Professional Paper 577 by Frank G. Lesure, 1968).

Many of the pegmatite bodies in the Spruce Pine District appear to be late-stage crystallization-differentiation products of larger granodiorite intrusives. These pegmatites contain a greater variety and abundance of rare elements, such as beryllium, cesium, fluorine, lithium, niobium and tantalum, than the “average” Blue Ridge pegmatite. The larger granodiorite intrusives are possibly the result of local melting and migration of magma and in an area of high-grade regional metamorphism during Paleozoic tectonic events. Other pegmatites, including that at the Cattail Mine that are not found near larger intrusives may have also originated from local melting of country rock at great depths, but on a much smaller scale. The mineralogy of these simpler pegmatites is generally lacking in rare elements. The molten rock that would crystallize to form the granodiorite intrusives and pegmatites was generated at great depth and under intense pressure that forced it into faults and fractures of preexisting rock. (from “Mica Deposits of the Blue Ridge in North Carolina, Geological Survey Professional Paper 577 by Frank G. Lesure, 1968).

I had determined by reading the USGS topographic map of the area that getting to the mine would be a strenuous hike of about 2-1/2 miles with an elevation gain of about 1,000 feet. Having lived in the southern Appalachians for over 15 years, I have become used to climbing up and down mountains to hunt for rock and mineral specimens. Often times the getting up to a collecting site is easier than coming back down due to a post-collecting pack full of heavy rocks. Although my wife, Chrissy, usually accompanies me on my rockhounding adventures, she opted out of this particular trip because she knows that her Miami, Florida heritage has left her a bit lacking of mountain climbing muscles. She sometimes jokingly refers to me as “goat boy” because of my seemingly mindless willingness to climb.

When I reached Rolling Camp Gap on Highway 197, I got my first view of the Black Mountains to the East and where I would be hiking that day. I was somewhat concerned about a thick coating of rime on the higher elevations; an icy white

blanket appeared to be covering everything at about the 5,000-feet elevation

mark. During the winter months in the southern Appalachians, you will often see white on mountaintops or up just one side of a mountain when water droplets in clouds or fog freeze to the trees forming rime ice. Often, rime can be

found only on the windward slope of a mountain as clouds carried by wind sweep over the ridge. Rime can create a winter wonderland for hiking as many times it will coat only the trees and tallest plants while leaving the ground dry, as I hoped would be the case that day. If the ground at the mine or along the roads and trails were also covered with snow and ice, rockhounding would not be possible – you can’t collect ‘em if you can’t see ‘em. But since rockhounding was not my only goal that day, I continued on my way with optimism.

found only on the windward slope of a mountain as clouds carried by wind sweep over the ridge. Rime can create a winter wonderland for hiking as many times it will coat only the trees and tallest plants while leaving the ground dry, as I hoped would be the case that day. If the ground at the mine or along the roads and trails were also covered with snow and ice, rockhounding would not be possible – you can’t collect ‘em if you can’t see ‘em. But since rockhounding was not my only goal that day, I continued on my way with optimism.

I drove up a steep and rocky road that switched back and forth along Cattail Creek into the Pisgah National Forest. I reached a gate where I parked and set

out on foot at around 4,200-ft elevation. As always when I hike anywhere new to me, I was armed with a compass, GPS device and a topographic map. I also

carried my digital camera to capture images of the day and a few rockhounding tools, including my trusty 6-pound sawed-off sledgehammer, a pointed chisel and a modified mattock. The day’s hike was over high-grade metamorphic terrain where excellent kyanite crystals in quartz and minor pegmatites can be found

scattered throughout the forest, so I kept my eyes peeled for signs of blue while I worked my way up on the old road to the mine.

I drove up a steep and rocky road that switched back and forth along Cattail Creek into the Pisgah National Forest. I reached a gate where I parked and set

out on foot at around 4,200-ft elevation. As always when I hike anywhere new to me, I was armed with a compass, GPS device and a topographic map. I also

carried my digital camera to capture images of the day and a few rockhounding tools, including my trusty 6-pound sawed-off sledgehammer, a pointed chisel and a modified mattock. The day’s hike was over high-grade metamorphic terrain where excellent kyanite crystals in quartz and minor pegmatites can be found

scattered throughout the forest, so I kept my eyes peeled for signs of blue while I worked my way up on the old road to the mine.

It took me about an hour to follow the road up to about a mile above sea level where the mine shaft was located. The mine opening was a large gaping hole on one edge of some relatively level ground with a drop of what appeared to be about 60 feet to a rocky flat area. I stayed well clear of the edge of the shaft but managed to peer down into the dark interior. A series of thick horizontal mine timbers spanned the far side of the pit. Although I could not see from my vantage point, this must be where the mine shaft extends downward to a depth of 210 feet below grade where it intersects the horizontal tunnel.

I made my way out to the nearby spoil piles that are draped from the level area down the steep southern slope.

The views to the east, south and west were spectacular; I could clearly see the Black Mountain ridge extending from Mt. Celo all the way to Mt. Mitchell to the south. I could barely make out the radio towers on the eastern end of Big Pine Mt., to the southwest of Mt. Mitchell.

The higher elevations were a sea of sparkling white rime with large swaths of evergreens where the ice didn’t take.

A view like that made it easy to forget about the rocks and I decided to head further up the road to where I hoped would be even better views of the countryside.

I returned to the road and continued to climb. When I reached about 5,300-feet elevation, the surrounding trees were completely covered in rime. It was like entering a walk-in freezer as the temperature dropped 20 degrees in a matter of just a few feet.

After managing to capture a few more pictures of the view from the road, I headed back down the Cattail’s spoil piles to see what I could find. I also wanted to locate and photograph the historic horizontal tunnel.

As I carefully made my way down and across the spoil piles, it became evident that this pegmatite was relatively simple and did not appear to contain the exotic minerals that other complex pegs do. The rock consisted primarily of feldspar, quartz and muscovite with a minor amount of scattered small red almandine garnets. It didn’t take long to discover that the Cattail, although famous for its monster muscovite crystals, would never become a premier rockhounding location, at least so far as for collectible mineral specimens is concerned. This is not to say that there wasn’t a gem or two hiding somewhere in the rough, but past experience with other similar pegmatites has taught me that my rockhounding time would be better spent at more obviously productive sites.

I continued down the steep rock strewn slope until I came upon the entrance to the mine tunnel.

In my prior research, I had discovered a 1952 newspaper article (shown in 5th paragraph) that contained a picture of the tunnel as it had appeared at that time. My first site of the tunnel was like a step back in time. While some slumping had taken place on the outer perimeter of the mine, the tunnel was completely intact and open. The rock wall above the entrance looked remarkably the same as the 55-year old picture. The complete lack of any timbers or fallen rock inside the tunnel indicated to me that it might have been reasonably safe to enter. But I wasn’t prepared to walk in the 2-feet deep icy-cold water nor did I bring a decent flashlight and the 47 backup

In my prior research, I had discovered a 1952 newspaper article (shown in 5th paragraph) that contained a picture of the tunnel as it had appeared at that time. My first site of the tunnel was like a step back in time. While some slumping had taken place on the outer perimeter of the mine, the tunnel was completely intact and open. The rock wall above the entrance looked remarkably the same as the 55-year old picture. The complete lack of any timbers or fallen rock inside the tunnel indicated to me that it might have been reasonably safe to enter. But I wasn’t prepared to walk in the 2-feet deep icy-cold water nor did I bring a decent flashlight and the 47 backup

lights it would have taken for me to feel comfortable venturing into the complete darkness. Besides, I knew that entering old mines is generally risky business and should certainly never be done alone. Moreover, I knew that the

tunnel extended some 525 feet into the mountain and that there was at least a 60 feet vertical shaft at the end just waiting to swallow someone up.

lights it would have taken for me to feel comfortable venturing into the complete darkness. Besides, I knew that entering old mines is generally risky business and should certainly never be done alone. Moreover, I knew that the

tunnel extended some 525 feet into the mountain and that there was at least a 60 feet vertical shaft at the end just waiting to swallow someone up.

After taking a few photographs and listening for distant voices, I felt that it was time to descend to my waiting truck. Although the Cattail didn’t offer much in the way of collectible minerals, the rocky road and forest were generous as I managed to find a few decent kyanite-bearing rocks along the way.

The pale blue color of the kyanite will always be a fitting reminder of a hazy afternoon sky above sparkling white trees.