Yancey County, North Carolina

By Mike Streeter

December 2011

(mcstreeter@charter.net)

|

Hurricane Ivan, the second powerful tropical storm in ten days, descended upon western North Carolina with a vengeance in mid-September 2004. Not even the old-timers could remember ever having seen it rain so hard for so long and this on top of already-saturated ground from the previous storm. Usually peaceful creeks and rivers quickly grew into violent torrents of water that wiped out just about everything in their paths, including roads, bridges and buildings. Before the dark clouds parted, the destructive effects of too much rain wreaked havoc on the entire mountainous region. Many millions of dollars were lost and untold lives were forever changed as massive floods and killer landslides devastated entire communities.

The Ray Mica Mine was especially hard hit by the storms. As much as 17 inches of rain was recorded at area monitoring stations in a 36-hour period. The small stream that runs through lower portions of the mine's massive spoil piles turned into a raging river. The incredible force of the water picked up and carried boulders and rocks of all sizes and other debris, and the stream cut down as much as 7 feet. It was ironic that the flooding event that had brought misery to so many mountain communities turned out to be a boon to rockhounds as rocks and minerals that had not seen the light of day since they were dumped during decades-old mining operations had been exposed. For the years that followed, Chrissy and I did quite well at the Ray by taking advantage of Mother Nature's fury and concentrating most of our digging efforts along the creek. According to a February 18, 2011 notice from the US Forest Service, Pisgah National Forest, Appalachian Ranger District, a specific area for rockhounding at the Ray Mine was designated; it is north of the un-named creek that flows through the base of the spoil piles. Rockhounding (any sort of digging) outside the designated area, including along the creek, was disallowed. With this, our days of digging along the creek had come to an end and it was time to return to the rocky slopes above the creek where I had collected off and on for nearly two decades. I had the Friday before Christmas 2011 off from work, so I decided to take advantage of the weather forecast that called for a well-above average temperature by getting up early to head out to the Ray Mine. Chrissy had to work, so I was on my own for the day. The small parking area at the head of the Ray Mine trail was empty when I arrived just after sunrise. I hiked the 1/2-mile trail to where it intersects the creek. |

|

|

|

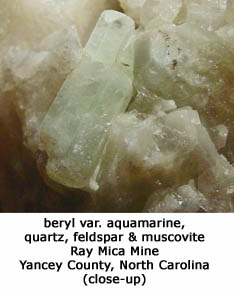

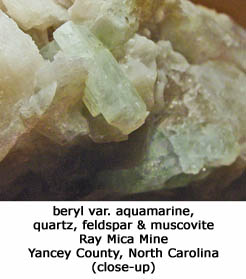

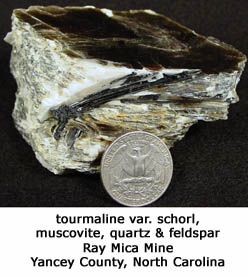

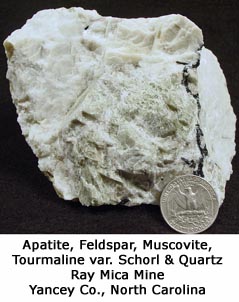

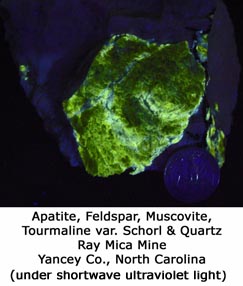

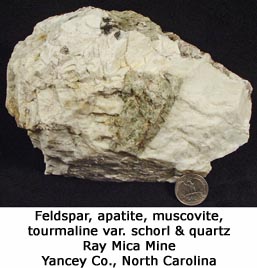

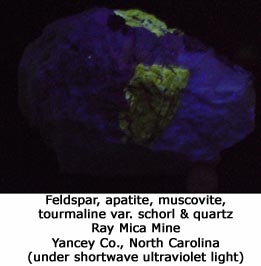

I surface collected along the creek for a couple hundred yards before picking my way a steep slope covered in jagged rocks. Having collected at the Ray more times than I can count, I looked for spot that contained what I consider the right type of pegmatite with a greater percentage of exotic minerals, including beryl. By the "right type", I mean a course grained pegmatite with tourmaline var. schorl, muscovite, albite, microcline and smoky quartz. I found a spot on the steep slope that felt right to me and set up shop and got to work.

My rockhounding method of choice at the Ray involves digging down to the untouched rock where there is little to no fine grained material. I have found that the very best layers are where the rocks and boulders look as though they had been dumped by miners, washed by rain and then buried beneath more rocks many decades ago. Getting to this untouched layer that can be as much as 15 feet below grade requires a great deal of effort. Great care must also be taken so as to not get buried by an avalanche of rock. As you can see in the following pictures, I dug a mighty hole - measuring from the top to the bottom and using the shovel as a scale, the pit looks to be about 12 feet deep, although sloped an appropriate angle to stop it from caving. |

|

|

|

|

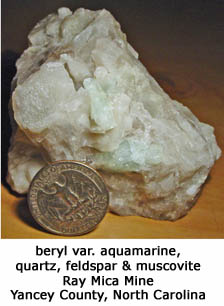

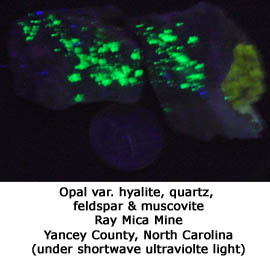

Although moving this great volume of rock and dirt was the cause of a future backache, I was rewarded with lots of goodies as shown in the following pictures.

|

(click on each picture to enlarge)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

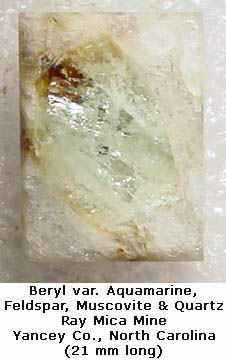

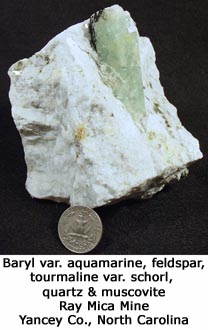

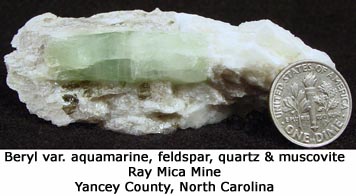

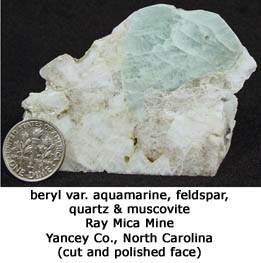

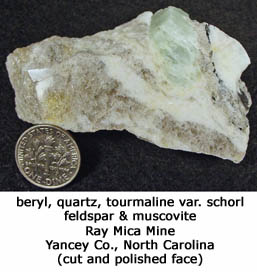

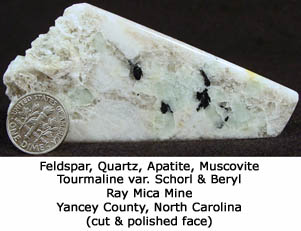

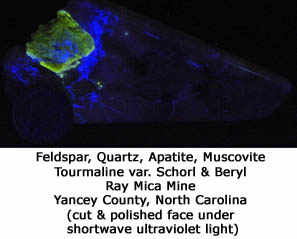

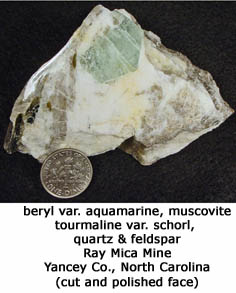

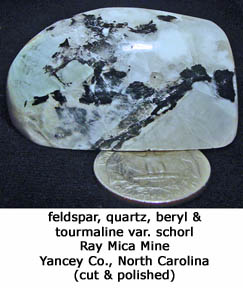

Due to the nature of the rock and it having been blasted, the vast majority of beryl and other minerals are most often found broken. When beryl is found whole in a rock, proper cobbing, so as to not destroy a specimen, takes experience, patience, nerve and a bit of luck. Some suggest that it would be better to take a rock home to employ some sort of hydraulic rock splitter for cobbing, but the size of the boulders and the over 1/2-mile hike back to the truck makes this an undesirable option for me. Knowing when to stop cobbing so that you don't ruin a specimen also takes experience along with discipline. No doubt, I have ruined many a specimen by giving it one too many whacks in an attempt to make it "perfect". But, the way I figure it, you have to lose some to get a few and I prefer to do my losing in the field. But, since I started making cabochons a couple years ago, I've found a way to improve the look of some broken Ray Mine specimens by cutting and polishing them; once borderline keepers are transformed into nifty shelf specimens as illustrated in the following pictures.

|

(click on each picture to enlarge)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

And speaking of making cabochons, the loose bits and pieces of rocks make for great lapidary material.

|

| Cabochons (cab pictures do not enlarge)

|

|

One of my favorite things to look for while surface collecting and digging is moonstone and sometimes I get lucky with extras like schorl inclusions.

|

|

As I made my way down the mountain to the parking area, I was pleased to see the creek flowing strong and clear. Hopefully, this will also please the USFS rangers so we rockhounds will be allowed to do what we do at the Ray for many years to come.

|

|

|

Please remember, no digging whatsoever is allowed along the Ray Mine creek or in its banks, just no-impact surface collecting only!!!!

|