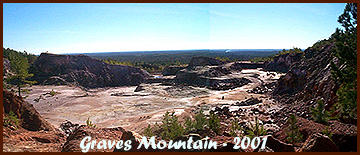

Graves Mountain is considered by many to be the "Mecca" of Georgia rockhounding

due to an incredible variety of minerals that may be collected there, including rutile,

hematite, goethite, pyrophyllite, lazulite, variscite, pyrite, kyanite, quartz, and woodhouseite.

The rutile is hands-down the finest and largest in the world. Brilliantly colored iridescent hematite

can be found as a coating on many of the mine's rocks and minerals. Although Graves Mountain

once stood as the tallest and largest hill in the area, what remains after over two decades

of mining, are two large pits that are as deep and they once were high, with a small portion

of the highest eastern point still standing above it all. Separating the east and west pits is an

area referred to as the "saddle".

hematite, goethite, pyrophyllite, lazulite, variscite, pyrite, kyanite, quartz, and woodhouseite.

The rutile is hands-down the finest and largest in the world. Brilliantly colored iridescent hematite

can be found as a coating on many of the mine's rocks and minerals. Although Graves Mountain

once stood as the tallest and largest hill in the area, what remains after over two decades

of mining, are two large pits that are as deep and they once were high, with a small portion

of the highest eastern point still standing above it all. Separating the east and west pits is an

area referred to as the "saddle".

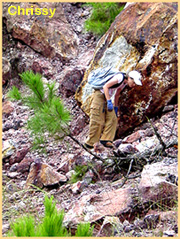

Although we have been to the mine literally dozens of times, Chrissy and I almost

never pass up an opportunity to dig there. So, after shooting the breeze with friends on Saturday morning,

we geared up and headed off toward the east pit. Although I usually carry all of our tools, buckets

and other gear with a hand cart, a thick accumulation of sticky mud caused by the previous day's

heavy rain made doing so impractical. We grabbed what tools we could carry and headed off toward

the generally less traveled east pit. Our rockhound, Opal, seemed to enjoy the wet conditions as

she ran ahead doing nothing to avoid splashing through the mud.

I had originally planned to walk around and prospect the mine due to a recurring

injury to my neck and upper back. I thought that maybe if I was to take a break from digging for

longer than 2 weeks, perhaps my injuries would have the proper time to heal. HA! It took me

all of about 5 minutes before I was swinging my mattock and stabbing a way at a portion of a wall

with my prybar. So much for healing that day! Of course, Chrissy was not surprised to look up

to see me digging away and she laughed and shook her head before moving on to do some actual

prospecting elsewhere in the east pit. When she wasn't confined by her leash, Opal spent her time

going back and forth between Chrissy and me.

injury to my neck and upper back. I thought that maybe if I was to take a break from digging for

longer than 2 weeks, perhaps my injuries would have the proper time to heal. HA! It took me

all of about 5 minutes before I was swinging my mattock and stabbing a way at a portion of a wall

with my prybar. So much for healing that day! Of course, Chrissy was not surprised to look up

to see me digging away and she laughed and shook her head before moving on to do some actual

prospecting elsewhere in the east pit. When she wasn't confined by her leash, Opal spent her time

going back and forth between Chrissy and me.

Chrissy came over to show me some fantastic green pyrophyllite that she had

found. Although white and beige colored pyrophyllite is relatively common at Graves Mountain, the

green variety is somewhat rare so that it was quite an excellent find - and, she had found a bunch

of it!

Click on each specimen picture above to enlarge

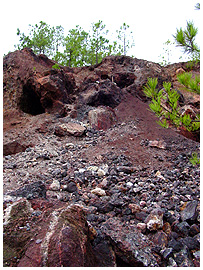

After poking around on several places and the steep high wall, I decided to pull

down an apron of rock and dirt that was blanketing a section near the top. By this time, Ron and

Faye Burke had made their way into the east pit and were working a section of the lower wall looking

for goodies. After I dug down to the bedrock, I discovered a fairly large quartz vein. I decided

to follow it hoping that it would contain pockets with quartz crystals and goethite. Before too

long, I started to find relatively small pockets that contained mostly goethite and some small

quartz crystals that were covered in iridescent hematite. When Ron saw the good stuff that I was

finding, he asked me what made me dig in that particular spot. I would have liked to have claimed

that I had a premonition or that my finding this particular vein was due to my superior knowledge of the

Mountain. But the truth of the matter was that I simply did not know what prompted me to pick this

spot. I have a theory that my rockhounding success is like that of a squirrel hunting for acorns

that it buried months before. A squirrel doesn't remember where it buries its acorns, but if it

digs enough holes it will eventually find one. Like the lowly squirrel, I figure that if I dig

enough holes, I'm bound to find my own "acorns".

for goodies. After I dug down to the bedrock, I discovered a fairly large quartz vein. I decided

to follow it hoping that it would contain pockets with quartz crystals and goethite. Before too

long, I started to find relatively small pockets that contained mostly goethite and some small

quartz crystals that were covered in iridescent hematite. When Ron saw the good stuff that I was

finding, he asked me what made me dig in that particular spot. I would have liked to have claimed

that I had a premonition or that my finding this particular vein was due to my superior knowledge of the

Mountain. But the truth of the matter was that I simply did not know what prompted me to pick this

spot. I have a theory that my rockhounding success is like that of a squirrel hunting for acorns

that it buried months before. A squirrel doesn't remember where it buries its acorns, but if it

digs enough holes it will eventually find one. Like the lowly squirrel, I figure that if I dig

enough holes, I'm bound to find my own "acorns".

By the middle of the afternoon, I had recovered a minor pile of decent material

from a series of relatively small and spotty quartz pockets. I was satisfied with my take but kept

digging for the fun of it. My neck and back were not talking to me so far that day, so I decided

to take full advantage of their silence. I pried loose yet another chunk of quartz from the vein

to see what was behind it and lo and behold I looked down to see that I had removed the cap from

a very large pocket. Most pockets in the east pit are collapsed so that it can sometimes be

difficult to tell that you have hit one. The tell tale signs are loose rocks and crystals including

"floaters" of stalactitic goethite. If a pocket is large enough, it will look like a small cave

with piles of material on the bottom and some cave-like formations and quartz crystals protruding

from the sides and roof. The pocket that I had discovered was completely collapsed with little air

space. With great care, I was able to extract dozens of loose and attached quartz crystals and

a pile of botryoidal and stalactitic iridescent goethite/hematite specimens. Some of the more

noteworthy specimens can be seen on the following page.

Report continued . . . . . . .

Click Here for Next Page